Border carbon adjustments are gaining momentum in Washington as a way to reward trade in low-carbon goods and boost clean, U.S. manufacturers. To implement a fair and effective border adjustment system, we need an accurate accounting framework that allows us to appropriately adjust for the emissions associated with making a good when it enters the U.S. market or is exported by a U.S. manufacturer. We propose a “cradle-to-border” accounting framework for carbon emissions.

Current emissions reporting takes various forms. The United States, for example, reports emissions from the electricity, industrial, transportation, and residential sectors based on data submitted by large facilities and fuel suppliers.

Many companies also engage in voluntary reporting, which often takes the form of “cradle-to-grave” reporting. This reporting captures on-site emissions; the emissions associated with energy purchases; and, when possible, the emissions associated with material inputs, product usage, and product disposal.

For a car, cradle-to-grave emissions accounting would include the emissions associated with producing all the steel, aluminum, glass, and other materials used as inputs, as well as emissions from assembly and shipping. It would also capture the emissions that the car is likely to produce during its useful life, plus any emissions associated with disposal. This broad accounting is also referred to as life-cycle analysis.

A border adjustment is designed to address emissions that occur prior to importation or exportation. An appropriate accounting framework for a border adjustment should ensure that imports can be held accountable for emissions associated with the good’s manufacture and transportation before arriving at the U.S. border. Likewise, exports are credited for any carbon, regulatory, compliance, or border adjustment charges incorporated in the cost of a good bound for a foreign market.

Full life-cycle analysis is useful in many contexts but is overly inclusive for a border adjustment. Here’s why.

Let’s return to the car example. When an imported car is driven in the U.S., all the emissions associated with powering the vehicle are already accounted for in data on domestic fuel sales and electricity generation emissions. Likewise, any freight emissions to bring the car from the port of entry to the dealership where it is sold, as well as any end-of-life emissions, are captured in domestic emissions data. So, a full life-cycle analysis to apply a border adjustment for a product like a car would double count any emissions that occur after it is imported.

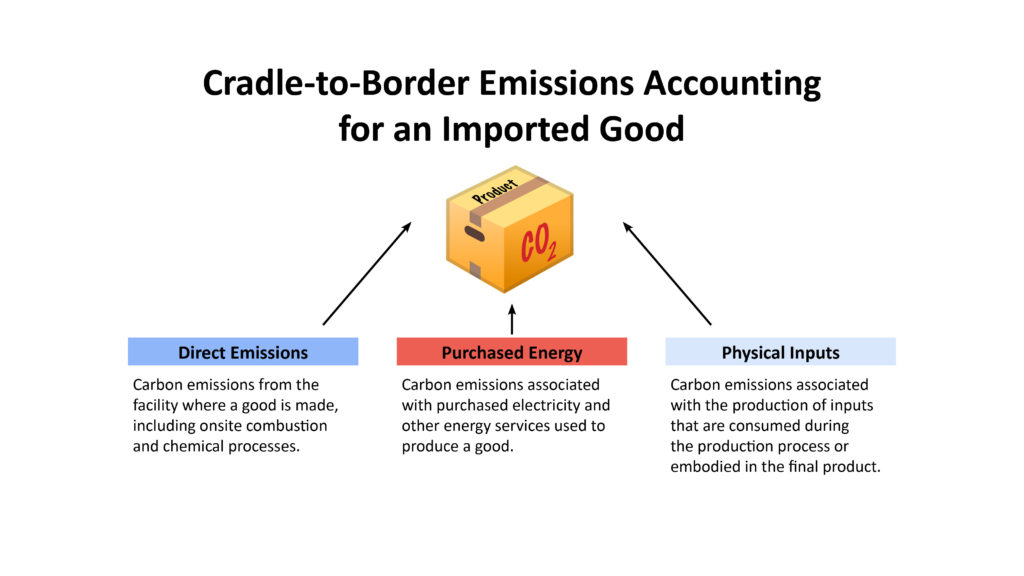

By contrast, the cradle-to-border approach counts only the relevant emissions. Applied to imports, this accounting standard captures the emissions generated outside the U.S. that are associated with manufacturing a good and bringing it to the border. For exports destined for a foreign market with different energy and climate policies, the cradle-to-border standard would capture all the emissions associated with making a good up until the point it is exported.

There’s also the scope of emissions to consider. If the border adjustment aims to capture all greenhouse gases, we might rely on the “Greenhouse Gas Index,” a measure of greenhouse gas intensity that includes non-CO2 gases such as methane and hydrofluorocarbons. If the border adjustment captures just those emissions for which we have relatively robust international reporting, we would restrict the accounting framework to CO2 emissions.

Most of the data we need to estimate cradle-to-border emissions is publicly reported, and the rest is collected by industry. Assuming appropriate access to data, a cradle-to-border accounting standard would capture:

- Onsite combustion and process emissions from facilities used in the manufacture of a good;

- Emissions associated with energy (e.g., electricity or steam) consumed during the production process; and

- Emissions associated with the production of inputs that are consumed during the production process or embodied in the final product.

It also includes, at least in principle, transportation emissions between points in the production process and in getting the final product to the U.S. border.