Over the past two years, U.S. lawmakers have expressed growing interest in border carbon adjustments (BCA), pollution import fees, and new trade deals to charge products based on carbon intensity. Abroad, the EU voted to approve its own Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, or CBAM, and other countries like the UK, Canada, and Japan are exploring their own policies. As interest in climate and trade policies continues to grow, it is important to understand why lawmakers are so interested in them.

BCAs, foreign pollution fees, carbon import fees, CBAMs, carbon tariffs—they all have different priorities and approaches, but they share common DNA: they all impose a fee on imported goods based on the carbon emitted to create that good. Said differently, they are all some form of a carbon intensity import fee.

So, why a fee on imports?

A fee creates a global incentive for manufacturers to reduce their emissions while leveling the playing field for those—including many manufacturers in the U.S.—who have already made significant investments to operate more cleanly. In this way, carbon intensity import fees have the potential to reshape international trade to meet our global climate goals, all while benefitting U.S. workers and manufacturers.

To understand more about why a country would want a carbon intensity import fee, it’s important first to understand the problem with our current approach to climate and trade policy…

The current international trade structure favors low-cost, high-carbon goods. There’s no mechanism for valuing the difference in the carbon intensity of goods or rewarding manufacturers who make the effort to operate more efficiently. This puts countries like the U.S.—who have made investments in cutting carbon emissions—at a competitive disadvantage compared to countries who have invested less in decarbonizing their economies. But a carbon intensity import fee would flip the script and turn those investments into an advantage. To understand how, let’s look at the U.S. steel industry.

The U.S. steel industry has a major carbon advantage. It’s able to produce the same amount of steel while emitting less carbon than its competitors. However, under the current international trade system, imported steel (i.e., steel from China and Russia) is cheaper than U.S. steel. This is because imported steel is produced using cheaper, higher-emitting processes and fuels. Conversely, U.S. steel is less carbon intensive to produce, but it faces competitive headwinds from producers in countries with lower environmental standards, cheaper labor, and some who deploy unfair and uncompetitive practices. Under the current trade system, if imported steel is cheaper to produce, then it’s cheaper to buy, and consumers will continue to purchase it, despite its larger carbon footprint. This is bad for the climate and U.S. businesses.

A carbon intensity import fee changes that.

A carbon intensity import fee would charge a fee on imported steel based on the carbon emitted during its production. In doing so, the carbon intensity import fee would unlock a competitive advantage for the U.S. steel industry. The high-emitting imported steel would lose some of its pricing edge, and the more efficient U.S. steel would occupy a greater share of the U.S. market, rewarding domestic workers and manufacturers for their low-carbon investments. As imports decline, the carbon intensity import fee presents foreign manufacturers with a choice: lower their emissions or risk getting priced out of the U.S. market altogether. In essence, a carbon intensity import fee levels the playing field to reward more carbon-efficient, U.S. steel manufacturers.

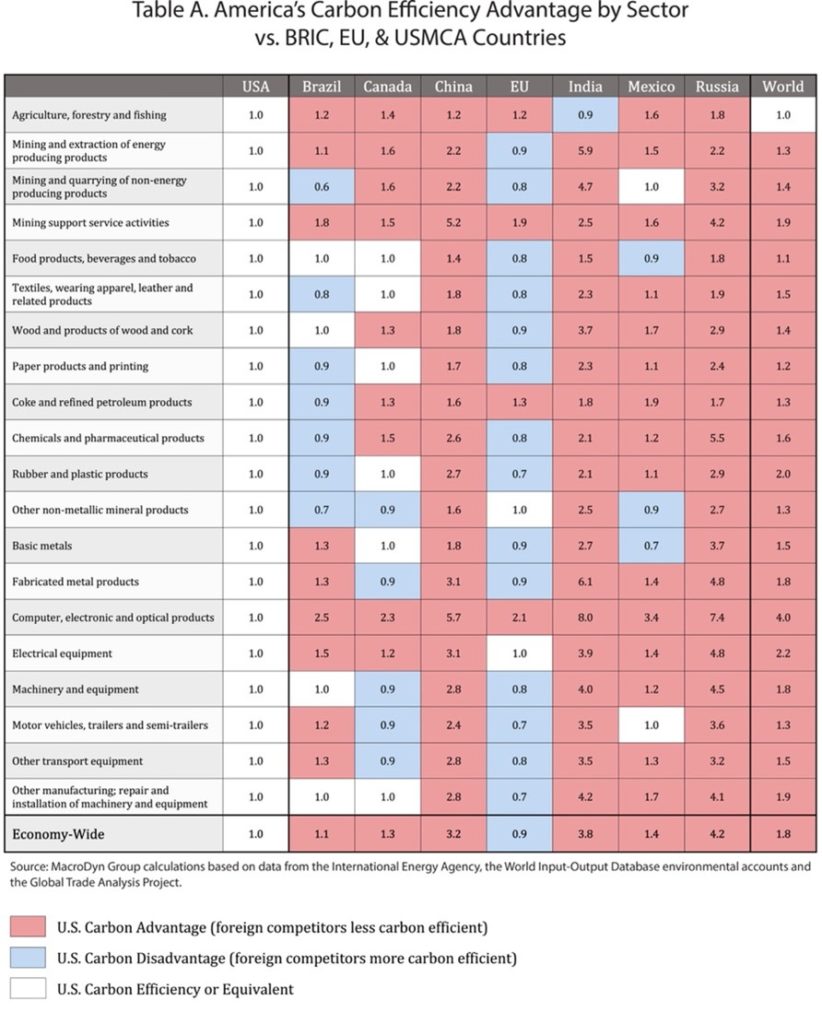

But the U.S. doesn’t just have a carbon advantage in steel manufacturing. As research from the Council shows, the U.S. is dramatically more carbon-efficient than its key competitors across nearly every manufacturing sector. In the case of the world’s largest exporter, China, the U.S. is 3x more carbon efficient. A carbon intensity import fee would dramatically benefit U.S. workers and manufacturers across the economy.

But that’s not the only benefit.

One of the critiques of current climate policies is that they lack international enforcement mechanisms. Under the current system, country A can enact policies to reduce their own carbon emissions, but they can’t do anything to lower country B’s emissions. But by charging imports a fee based on their emissions, a carbon intensity import fee would allow countries like the U.S. to hold high emitters like China and Russia accountable and incentivize them to reduce their emissions. A carbon intensity import fee would allow the U.S. to lower global emissions while benefitting its domestic, carbon-efficient manufacturers.

In doing so, we would also strengthen ties with like-minded countries who share our ambition. As mentioned earlier, the EU, UK, Canada, and Japan have all taken steps to explore or implement their own climate and trade policies. By working together to reduce emissions through trade, we would promote greater international cooperation—an essential component of solving the climate challenge since no single country can do it alone.

Additionally, a carbon intensity import fee would help secure valuable supply chains by encouraging manufacturers to produce more goods at home, where it would now be cheaper and more carbon efficient.

Because of these benefits, it’s not surprising that lawmakers’ interest in carbon intensity import fees is growing. But as that interest grows, so do questions about the policy. Questions such as:

- How would the associated fee be calculated?

- What would countries do with the revenue raised from the carbon intensity import fee?

- How could the U.S. coordinate with other countries or regions to avoid trade disputes?

To help sort through these decision points, the Council developed a primer to address some of the other questions about carbon intensity import fees and inform lawmakers as they consider their own carbon intensity import fee proposals.

While there are still many details left to iron out, one thing is certain—carbon intensity import fees will play a major role in shaping the future of global climate and trade policy. By charging imports a fee based on their emissions, these policies have the potential to cut global emissions, benefit U.S. workers and manufacturers, secure valuable supply chains, and reshape the global trade paradigm for the good of the climate. These outcomes hold bipartisan appeal and are starting to bring a diverse coalition on board with the idea.