China holds more than half the global market for steel manufacturing. Recent data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) suggests that Chinese manufacturers have ramped up their exports to global customers by 83% in recent years.

This blog explores how the persistent investment in Chinese excess capacity, driven by long-standing non-market practices that support low-cost, high-emissions iron & steel manufacturing pathways, is impacting the global marketplace to the detriment of global competition and efforts to reduce emissions. Market dominance by less efficient firms is one of the reasons that policymakers and industry are exploring carbon import fees and related policies.

Excess capacity is a challenge for the market and the climate

The Chinese Community Party (CCP) subsidizes steel production at a rate ten times higher than the OECD average through below-market lending, subsidized energy prices, direct grants, and preferential tax treatment. While it is normal for manufacturers to occasionally outpace (or underserve) market demand, excess capacity that persists over time is often indicative of persistent anti-competitive government intervention. This is non-market excess capacity (NMEC).

Interventions by the CCP keep inefficient steel mills running and drive new investment into steel capacity that would not be commercially viable under normal market conditions. The result is a persistent surplus of steelmaking capacity in China. This chronic excess capacity puts downward pressure on global prices.

Moreover, trends toward NMEC are set to continue. OECD’s 2025 Steel Outlook found that steelmaking capacity worldwide is expected to increase by another 7% between 2025 and 2027 despite sluggish demand. Asian economies are expected to account for 58% of the new capacity, with China leading new additions domestically and through cross-border investment.

In addition to distorting market dynamics, NMEC drives excess greenhouse gas emissions from the global steel industry in four primary ways:

- Enables inefficiency: sustains and incentivizes inefficient production pathways.

- Creates high-emissions clusters: concentrates production in regions with more emissions-intensive methods.

- Undermines efficient producers: collapses profit margins for more efficient competitors.

- Discourages innovation: impedes investment in process improvements and novel manufacturing approaches.

A new frontier for carbon-intensive Chinese steel: exports to emerging markets

Chinese firms are persistently out-competing international rivals on cost. According to OECD’s recent analysis, Chinese steel exports nearly doubled between 2019 and 2024. Over the same window, steel exports from the rest of the world decreased by 15%.

Further analysis using the Observatory for Economic Complexity (OEC) reveals that Chinese steel exports over the period grew most significantly in two ways:

- Exports are growing most significantly to emerging markets where steel demand is rising rapidly. Total Chinese steel exports to emerging markets increased by over 50%, compared to just a 15% increase to advanced economies.

- Exports are surging in lower-value, less processed unfinished steel. Chinese exports of unfinished steel goods increased 115% to emerging economies, indicating that domestic production capacity for these unfinished steel goods is outpacing what its own downstream market can absorb.

The expansion of China’s exports to emerging markets, particularly of unfinished steel goods, is further locking in carbon-intensive steel production. These exports are crowding out opportunities for emerging markets to develop modern, efficient steelmaking domestically or to import more efficient steel from producers like the U.S.

The surge in exports to emerging markets doesn’t discriminate by market size. Among the largest emerging markets, Chinese unfinished steel exports doubled to Vietnam, tripled to India, quadrupled to Brazil, increased sixfold to Turkey, and increased eightfold to Saudi Arabia (see Figure 2).

Exports similarly increased to smaller emerging markets across Africa and the Americas: doubled to Nigeria, Peru, Guatemala, Ecuador, Honduras, and the Dominican Republic; tripled to Egypt, Colombia, and Tanzania; and quadrupled to Djibouti.

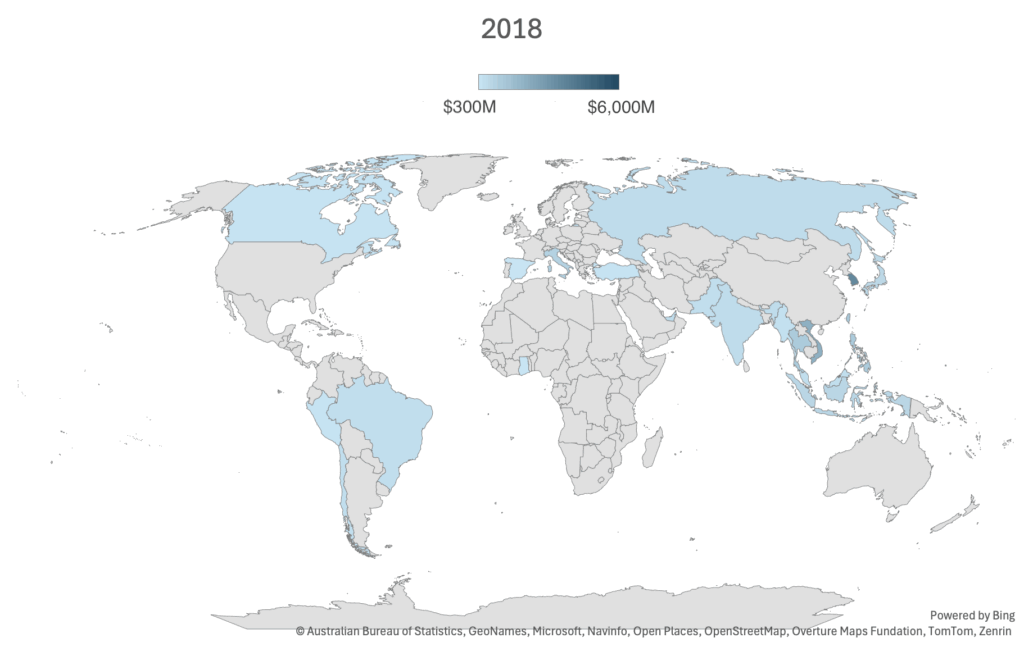

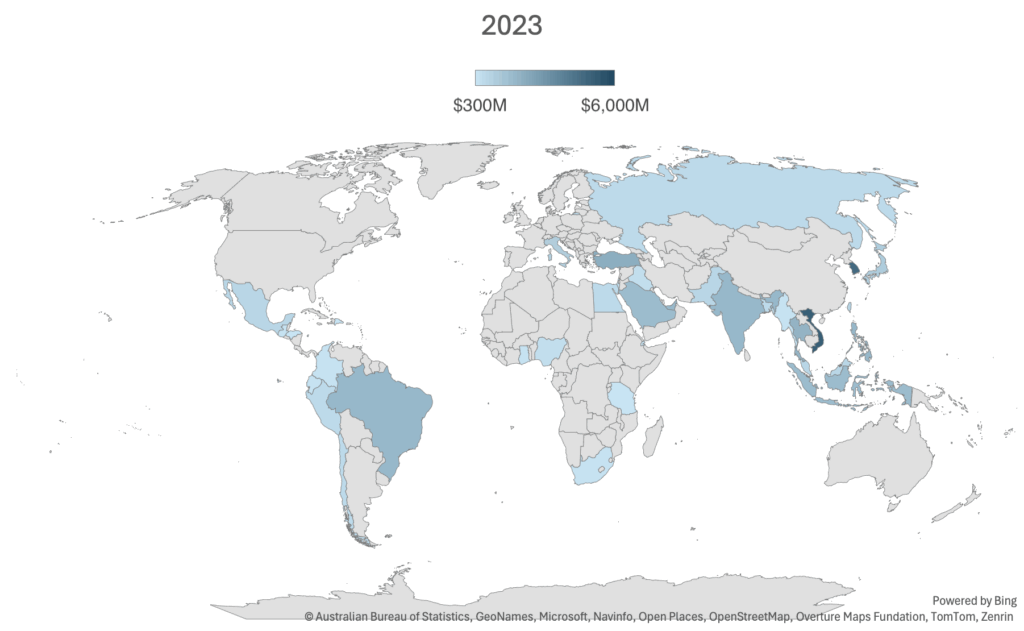

Figure 2: Growth in China’s unfinished steel exports by country, 2018- 2023.

Shading reflects each country’s net imports of unfinished steel from China. Maps include only countries that imported over $300 million of unfinished steel from China in each year.

We’re watching closely as Chinese excess capacity exerts new pressures on trade flows. As the CCP continues to invest in NMEC amidst sluggish demand, we may see a surge in Chinese exports of steel products even further up the supply chain like pig iron and other steel precursors. Appropriate checks on non-market practices through the global trading system will become increasingly valuable. Tools such as carbon import fees that account for both emissions intensity and NMEC can help to contain CCP control over global steel production and trade.