The EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), the world’s first carbon import fee on internationally traded goods, entered its inaugural phase on October 1, marking a profound transformation for the global trading system. During this “transitional period,” importers will have to report specific emissions information associated with the production of iron and steel, aluminum, cement, fertilizers, hydrogen, and electricity imported into the EU. Importers will be required to pay a fee on those emissions beginning in 2026.

The transitional period allows both importers and EU policymakers to adjust to new requirements as implementation is phased in. While some U.S. firms must already report facility-level emissions data, the CBAM requires importers to now report product-level emissions using a specific, novel framework and a new reporting system that will handle massive volumes of sensitive business information. Importers must also take the extra step of asking their suppliers outside the EU to collect and report information. The Council’s latest white paper provides deeper analysis on the design and global implications of the CBAM implementing regulation.

EU policymakers will learn how their preliminary emissions reporting rules work in practice; monitor the tension between flexible reporting requirements and precise, comparable data across goods and industries; and consider changes to the policy for the CBAM’s post-2025 definitive period.

As the transitional period progresses, we want to better understand how the CBAM may affect covered U.S. industries.

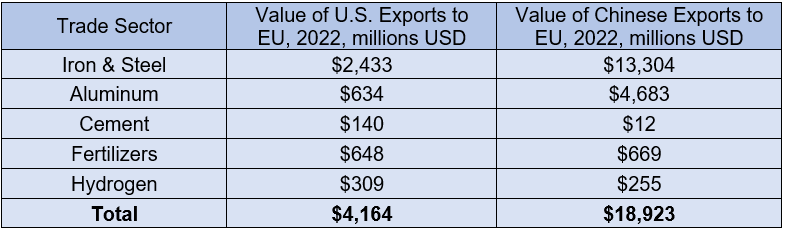

The CBAM will affect only a sliver of U.S. exports to the EU: of $350 billion of U.S. exports to the EU in 2022, just 1.1% ($4 billion) fell within the categories covered by the CBAM. In comparison, China, the EU’s largest partner in traded goods, exported nearly five times the value of CBAM-covered goods in 2022—$19 billion worth of exports to the EU. Table 1 examines CBAM-covered trade between the EU, the U.S., and China.

Table 1. Value of U.S. and Chinese exports to the EU in CBAM-covered categories, 2022.

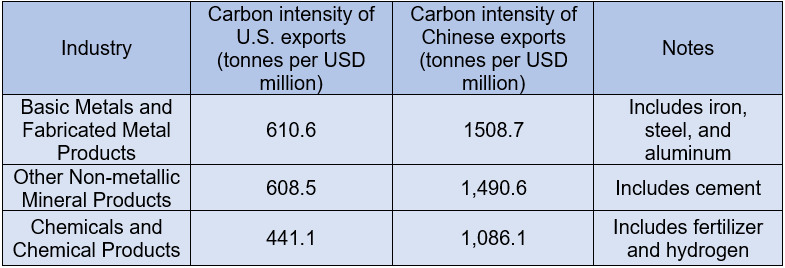

The U.S. is a much more carbon-efficient manufacturer of CBAM-covered products than Chinese competitors. In Table 2, we summarize the relative carbon-intensity of covered sectors between the U.S. and China—in other words, how much carbon is emitted to manufacture comparable products in one country versus the other. With Chinese firms trading larger volumes of relatively more carbon-intensive product, they are poised to see a larger CBAM charge once the price mechanism begins to phase in starting in 2026.

Table 2. Carbon intensity of U.S. and Chinese exports to the EU in product categories that include CBAM-covered products, 2018.

A quick analysis, applying a projected CBAM charge of $120/tonne of carbon emissions to EU imports suggests that Chinese imports will be affected roughly eleven times greater than U.S. imports. U.S. products entering the EU will face an estimated total charge of $0.3 billion; Chinese products entering the EU will face an estimated charge of $3.4 billion. As importers begin to pay a fee for their carbon emissions, U.S. firms are well positioned to out-compete Chinese firms in the European market, and the competitiveness of U.S. firms may even improve under the CBAM.

The U.S. doesn’t just beat out China in carbon intensity. Among the most carbon-efficient and productive economies in the world, the U.S. could very well displace imports from China and other trade competitors in the EU market. As our analysis shows again and again, when we introduce a system of accountability for the carbon intensity of traded goods, more efficient U.S. firms win.

These are simple estimates. The true impact of the EU CBAM on the U.S. will depend not just on the relative emissions intensity of traded U.S. products, but also on implementation issues, data quality, ease of compliance, and the appropriate treatment of confidential business information. Moreover, the first CBAM reports will be due on January 31, 2024. As importers begin to submit reports that are incomplete or inaccurate, they may face penalties of €10 – 50 per tonne of unreported emissions. While intended to solicit more complete reporting, the threat of compliance fees may subject U.S. manufacturers that are unwilling or unable to share sufficient information to price pressures.

We’ll continue to learn more about how the implementation of this novel policy impacts trade and U.S. firms, and we look forward to sharing more with you in the months ahead.